Introduction

Loyalty is an elusive historical concept. It is formed in an individual through a combination of social factors, including the influence of longstanding cultural elements, contemporary community standards and interpersonal relationships. Loyalty is difficult to gauge in societies at war, particularly those experiencing civil war, as the state or group in power defines and often changes acceptable expressions of patriotism or dissent. This process is made all the more difficult in liminal societies that harbour a variety of traditions and outlooks that may overlap and vie for supremacy within the individual. Indeed, what George Fletcher has illustrated as a bedrock idea of loyalty, the conscious rejection of one ideal or object in favour of another,1 others have elaborated upon, citing the fact that "modern man belongs to many tribes at once."2 That is to say, one's family, profession, finances, nation, country, culture and religion may all coexist, and even overlap, but each competes for primacy. Ultimately, while individuals' associations and behaviour may reveal the direction of his or her loyalties, this does not eliminate the coexistence of multiple, overlapping, or perhaps even conflicting, loyalties.

Ireland experienced a fundamental shift in its nationalist loyalty dynamic throughout the Great War and into the post-war, or "greater" war, period.3 The war may be seen as a catalyst to this, but in other ways it merely intensified popular militancy that had swelled in Ireland prior to 1914, evident in the formation of pro- and anti-Home Rule paramilitary bodies, the Irish and Ulster Volunteers, respectively.4 However, a split in the Irish National Volunteers over the question of Irish enlistment in the British Army helped to concentrate more advanced nationalist elements within a breakaway minority group, the Irish Volunteers. Plans for a national insurrection and the establishment of an Irish republic by the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army were realized on Easter Monday 1916. British forces put down the Easter Rising, which was confined to Dublin, Galway and several small pockets of revolt throughout the country, in one week. It nevertheless became a symbol of resistance and, to many, an admirable example of patriotism and sacrifice unique to that exemplified on the Western Front and throughout the world.

The Easter Rising also prompted a shift in Irish nationalist political loyalties as the separatist and isolationist ideology of the Sinn Féin party eclipsed the more traditional nationalist platform represented in the Irish Parliamentary Party (I.P.P.), which had supported Irish participation in the war and whose leaders encouraged enlistment. Rising nationalist sentiment, and the perceived threat of conscription, resulted in the I.P.P. losing all but six of its seats at the 1918 general election, while Sinn Féin won nearly fifty per cent of the vote and returned deputies in seventy-three of 105 constituencies.

This transferral was accompanied in the immediate post-war years by a formalized war on British authority in Ireland, waged by Volunteers in the Irish Republican Army (I.R.A.), and legitimized for many of its participants through the founding of Dáil Éireann, or Irish parliament, in early 1919.5 Both characterized elements of an Irish counter-state by weaving refined standard of republican loyalty, and rejection of British authority, into its program. The Irish War of Independence (1919-1921) was unlike the recently concluded global, industrial war. In addition to targeting British security personnel, the Royal Irish Constabulary (R.I.C.), British army regulars and, after 1920, Black and Tans and Auxiliary policemen, the I.R.A. enforced a standard of civic republicanism throughout much of southern Ireland through the physical intimidation, social ostracism, and murder of those it identified as enemies, including fellow-Irishmen and women and veterans of the Great War. The outcome was a variety of individually traumatic experiences as well as a general sense of unease within communities.

Trauma complements the study of loyalty in a number of ways. In addition to the mental stress associated with perpetrating or suffering violence in guerrilla-style conflict, onlookers and apolitical non-combatants experienced a variety of traumas during this period and afterward. These ranged from perceptions of sexual violence, fear of being labeled a traitor, intimidation, social and professional ostracism, and exclusion from state commemorations of the period. This paper examines the intersection of loyalty and trauma during the Great War and Irish Revolution. First, it explores contemporary definitions of nationalist loyalty in Ireland throughout the Great War, setting a foundation from which to examine the departure into republican loyalty after 1916. Second, it examines redefined concepts of loyalty throughout the Irish War of Independence and brief civil war period. Finally, it analyses aspects of trauma within the Free State, most immediately noticeable amongst two marginalized groups: anti-Treaty republicans and Irish veterans of the Great War.

Dual Upheavals: the Great War and Irish Revolution

The Great War made a significant contribution to the evolution of nationalist identity in Ireland. However, the war also complicated the narrative of the revolutionary period that overlapped it, and the foundation of the Irish Free State that followed it. Nearly a quarter-million Irishmen served in the British Army during the Great War; just less than 50,000 perished, meaning a sizable body of demobilized soldiers returned to an Ireland and elsewhere at a time when popular conceptions of nationalism had shifted, and where the definition of loyalty had become quite complicated.6

Radical outlooks and revolutionary organizations existed in Ireland prior to 1914, but by the twentieth century they represented a small strand of nationalist opinion.7 This is reflected in crime reports of the period, as well as within memoirs and statements of Irish constables, who considered their service prior to the Great War as peaceful, with life in rural parts of Ireland as being very pleasant.8 Their chief duties involved regular police work and the occasional suppression of illegal distilling.9

However, by August 1914 Ireland faced several domestic crises that threatened to spill over into civil war. Principally, the introduction of home rule legislation that would establish a devolved parliament for Ireland established in Dublin. This prompted resurgence in Unionist opposition to home rule, which had stabilized to a certain extent following violence protests in the 1890s. The Ulster Volunteer Force was founded in 1912 to resist Ulster's assimilation into what it perceived would be a Catholic-dominated parliament. A second paramilitary group, the Irish Volunteers, were founded in November 1913 to ensure that Home Rule indeed became a reality. Though organized locally, the group came to be dominated by Irish Parliamentary Party leader John Redmond, who assumed the role of president of the Volunteers in the summer of 1914 - a time when Britain's micro crisis over home rule competed with concern over the international situation developing on the continent.

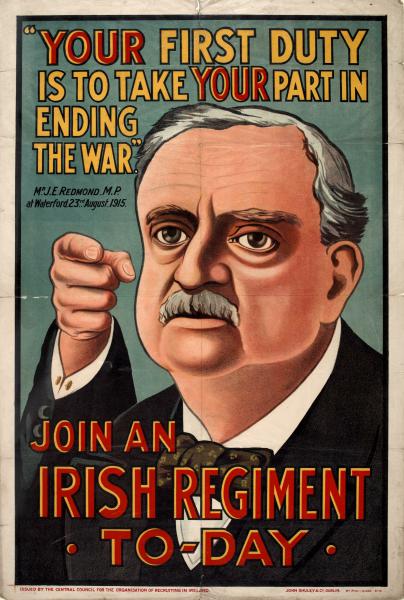

In essence, Britain's declaration of war on Germany in August 1914 defused the prospect of civil war in Ireland. Leaders of the Ulster and Irish Volunteer organizations respectively spun enlistment for the war as an extension of loyalty to Ireland, redirecting the would-be fratricide. Redmond considered the war as "the greatest opportunity that has ever occurred in the history of Ireland to win the Irish people to loyalty to the Empire."10 That is, enlistment in the imperial struggle against the Central Powers would demonstrate that a free Ireland would continue to support Britain. In September 1914 Redmond called for Irishmen to go "wherever the firing line extends" to defend Irish freedom.11 This speech may have resolved ambiguity of the Irish Volunteers' position toward the war, but it also alienated the more radical strand of nationalism within their ranks and amongst their supporters. For instance, the anti-imperialist Roger Casement considered Irish enlistment in the British Army a deposit on Irish freedom, or a promissory note "payable after death."12 He went on to explain how Ireland's involvement in the Great War was illogical: "It seemed to be the duty of all Irishmen who loved their country to do their utmost to keep Ireland out of this war," he said; "a war that had no claim upon their honour or their patriotism."13 Redmond's was a gamble that had mixed results, and one that ultimately aided in the narrowing of the definition of loyalty in Ireland during the Great War through the breaking away of the more radical faction of nationalists.

Separatists and advanced nationalists rejected Redmond's formula of loyalty - that which equated enlistment and the success of the Allies with Irish freedom. One radical newspaper, the Irish Volunteer, explained the fallacy of such a proposal:

"Our flag is green, and any man who cheers for another flag before he has done his utmost to have his own float over a free nation is a traitor. Any man who cheers the flag of our oppressor before they have made restitution to the nation is doubly a traitor."14

As the Irish Volunteer promised, Redmond was identified and unapologetically branded a traitor by the radical separatist press in the months that followed the outbreak of war in Europe.15 A piece of nationalist propaganda entitled "A ballad of European history" sang out:

"J is for John Redmond and Judas as well Betraying the Irish to Empire and Hell.16

Similarly, a satirical poem published in The Cork Celt carried forward the theme of nationalist duality, of those who would enlist in an effort to ensure the passage of home rule in Ireland, and those who rejected this notion of delayed nation gratification, that is, of home rule being suspended for the duration of the war:

"Oh! Paddy dear, and did you hear, the news that's going round, The Green Flag's a back number, everywhere on Irish ground, Our trusty Irish leader flies the English Union Jack, But God help our wives and mothers, they are mostly wearin' black. The Irish race gets pride and place on French and Belgian plains, Although the English Parliament has hanged Home Rule in chains, For Johnny Red[mond] has plainly said, the Irish Volunteers, Should go to France and fight beside the British Grenadiers."17

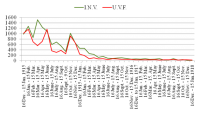

Despite lambasting from Irish nationalists, the question of enlistment as a form of demonstrable loyalty certainly carries some weight - most noticeably in the early years of the war. Kevin Kenny and others have reiterated the popular interpretation of enlistment by the rival factions of Irish National Volunteers (Redmond faction) and the Ulster Volunteers, as individual and collective declarations of loyalty to the empire in its time of need, and as a way to bolster support for their respective pro- and anti-home rule positions.18 Initial Irish enlistments, which exceeded 40.000 by December 1914, certainly speak to this end. The majority of these enlistments, however, came in the form of reservists. Wider trends in Irish enlistment reveal a general malaise by members of both Volunteer outfits, and the Irish public in general, with an obvious exception represented in strong returns following the concentrated Wimborne recruiting scheme in the autumn of 1915. The graph below illustrates this pattern of enlistment to 1917.19

Other explanations for enlistment, however, paint it as a normal individual expression of group conformity. As David Fitzpatrick explains:

"What drove most recruits into the war-time forces, apart from a desire for adventure and subsidised international tourism, was loyalty to their friends and families. It is, therefore, not surprising that [...] each member felt under strong psychological pressure to conform to group expectations."20

Consequently, enlistment may be seen as a result of established communal loyalties rather than effective propaganda. However, between 1916 and 1919 this ambiguity of allegiance would be clarified, as would communal pressure to conform to new ideals of patriotism.

The 1916 Easter Rising altered popular nationalist perceptions of service and sacrifice in Ireland. Although pro-British newspapers initially labeled the rebellion treasonous to those fighting in the trenches - particularly following the news of Roger Casement's attempt to secure German aid - by the late summer of 1916 its leaders had been transformed into martyrs for the cause of Irish freedom. In many ways the Rising's association with freedom eroded arguments presented at the outbreak of the Great War that enlistment in the British Army would help to achieve independence. Indeed, in the years that followed, the Rising and revolution it inspired supplanted the Great War as Ireland's chosen national trauma. That is, public perceptions of the sacrifices being made by the I.R.A. and Cumann na mBan, the women's auxiliary to the Irish Volunteers, superseded the services offered to King and Country in the Great War, and the casualties that resulted from it. 21 Collective conviction also influenced individual outlooks. Between 1916 and 1919 the expanding clique of republicanism meant actively supporting the Sinn Féin party, opposing conscription in Ireland, and ostracizing supporters of the British system, including Irish-born policemen, and families of those serving in the war.

If participation may be used to measure individual adherence to national and communal standards of loyalty, that is, actions and behaviours identified as aligning with an accepted definition of loyalty, then how might one account for participation in localized revolutionary violence in Ireland of the post-Great War period? Were such expressions of loyalty genuine or coerced, and how might loyalty and the actions stemming from it inform the study of trauma? This question has been only partially answered, though it continues to be explored. The scholarship of two authoritative historians, who conducted regional studies on the social origins of the Irish Volunteers as well as their motivation for joining the Irish independence movement and their participation in guerrilla warfare, contribute greatly to the study of allegiance in Ireland during this period. Joost Augusteijn and Peter Hart both examined the radicalization of the Irish Volunteers in the years following the Easter Rising.22 Each identified the development of group loyalty as stemming from communal intimacy and participation in revolutionary violence - factors that helped develop and nurture a sense of personal belonging, group exclusivity and overall interdependence.23 Such phenomena help to clarify responses to communal and national pressure to participate in violent conflicts, be they international or localized. This was, of course, not unique during a period that saw bonds of camaraderie forged in the harsh conditions of industrialized war. For instance, French historian Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau has explored some of the models and boundaries of camaraderie between French soldiers in the trenches during the First World War through their trench journalism. His assertion that interpersonal loyalty was a component of the "privileged relationship" between soldiers prompted by the stress of a broader conflict applies to the type of relationships formed within the paramilitary units of the Irish Republican Army.24 Hart deconstructed this mentality at the individual level:

"These men shared very real convictions and ideals, but it seems clear that, for the majority of Volunteers, the decision to join was a collective rather than individual one, rooted more in local communities and networks than in ideology or forming political loyalties. Young men tended to join the organization together with, or following members of their families and friendship groups. [...] Loyalty to "the boys" almost always proved stronger than loyalty to the organization."25

This sense of interpersonal attachment allowed the I.R.A. to develop as a regionally based and effectively decentralized guerrilla force from 1917 onwards while maintaining the defence of the Irish Republic as a broader mediator of unity. In short, participation was reinforced psychologically through the recognition that one played a single part in the broader independence movement. The revolution thus represents a "communal project," as described by George Fletcher and Josiah Royce, one that contributed to the construction of loyalty within individuals toward one-another, as well as toward ideals.26

Acts of violence helped strengthen the convictions of Irish society as well as I.R.A. guerrillas. Encounters with the enemy, whether British military or police, or, in the case of republican targets, the I.R.A., were at times intimate confrontations that took place in a variety of settings and spaces, ranging from quiet country roads and busy city centres, to sporting grounds and bedrooms.27

However, participation alone, no matter how intimate or idealistically driven, cannot act as the sole yardstick by which to measure loyalty. Fitzpatrick and Hart also explored the intensity of the guerrilla campaign in Ireland as depending on a variety of factors, including local initiative, availability of arms and ammunition, local cooperation, and the concentration of crown forces.28 Overall, while the I.R.A.'s guerrilla campaign may have aided in the creation and reinforcement of interpersonal and group-based loyalty dynamics, there existed a number of factors, often regionally based, that hindered its uniformity.

Prison was theatre of war where loyalty, violence and trauma converged. For many revolutionaries political imprisonment, or imprisonment for crimes deemed to be politically motivated, was a rite of passage and associated with honour.29 Violence committed in prisons represented not only continued efforts to disrupt the British administration in the name of the Irish republic, but strengthened personal bonds and solidarity. This is apparent in the variety of methods political prisoners used to assert their authority in the face of warders, including loud shouting and singing, the destruction of cells, direct assaults on warders, and self-immolation through hunger strikes. The frequency of these assertive acts increased between 1917 and 1920, after which hundreds of Irish prisoners were deported to gaols in Britain so as to be removed from an increasingly sympathetic Irish population.

Participation in prison émeutes, or riots, was a method through which one could display loyalty - not only to the cause of independence, but towards one's fellow-inmates. It is in this sense that we may understand "rolling" outbreaks of violence and hunger strikes in prisons, where one section of men would take up or join the protest so as to encourage or relieve the other. Such peer-inspired violence, both in and out of prison, also highlights the reality of directed, enforced, or coercive loyalty during the revolution, and the overall pressure to conform. A secret directive from Volunteer General Headquarters, discovered within a loaf of bread left for prisoners outside Maryborough (Portlaois) prison in 1919, illustrates such a directive.30 It read:

"Every Irish Volunteer at present in jail as the result of any activity connected with the movement is instructed to immediately demand and strike for treatment as a political prisoner. The strike should take the form of refusal to work, to wear the prison garb, to obey any prison regulation whatever, generally subvert prison discipline. It is to be noted that a hunger strike is debarred."31 The pressure to participate in acts of violence, and thus display one's loyalty to the cause, was great. As a result, the desire to commit violence against the prison, or against oneself in the form of hunger strike, was not always genuine. A quantity of intercepted correspondence between republican prisoners and warders speaks to this end, such as a letter from Felix Connolly to Charles Munro, Governor of Cork prison, written following a riot in 1920:

"Well sir I apologise sincerely to His Majesty's Government for my conduct as I didn't understand it, and you may be sure if I went on strike it was completely against my will."32

Pressure to conform was not only experienced by those who felt they might have acted against their conscience. In some instances, influential leaders also struggled. Frank Gallagher left a forceful account of this mentality in "Days of fear," which chronicles the first successful mass hunger strike in Ireland in 1920.33 Gallagher's account articulates the struggle to rationalize self-imposed starvation, the fear of being branded a traitor by his comrades for taking food, and the dual-torture of an empty stomach and a wandering mind. After approximately four days on strike, Gallagher explored the notion that death would be a welcomed change to the monotony which awaited him in civilian life: "There are better things than living to be an old and valued member of half a dozen public councils."34 His death would be a great service to the Republic, he thought; "By smashing their prison system we become free to continue the smashing in Ireland of their Empire. ... A few days' hunger in payment for such a blow is nothing. ... Even a few deaths from hunger is nothing."35

On 11 April, however, the medical officer determined Gallagher had reached the "danger point" - a state at which death was certain if nourishment was not taken. Confirmation of approaching mortality isolated Gallagher's patriotic motions, and his prime motivator is exposed as loyalty to the oath he and others had taken "to the honour of Ireland and the lives of my comrades not to eat food."36 Gripped with dread, uncertainty and experiencing the "double personality" common to those enduring hunger strike, Gallagher pondered, "Why should I die?":

"I am young and I can go away and change my name. ... Nobody would know nobody. ... If they found out I would deny it. ... But I would know that I had eaten. ... Wherever I went that knowledge would be inside me ... the thought of it ... the feel of it ... making me an outcast to myself ... driving me mad. ... Everybody would see it, written flamingly all over me, that I had betrayed those who trusted me ... those who scorned to dodge death ... I would want to die then, and I could not.37

Gallagher's fear eventually passed, but not before physical weakness and self-doubt had consumed him. He was discharged on the tenth day of his protest; nearly all of his fellow-strikers were subsequently released or paroled. Cleric and comrade alike applauded their efforts, strengthening broader popular approval of such protests and the sacrifice they represented. Father Albert (who had attended the rebels of Easter Week), extended his "love and blessing" to the strikers; Gearoid O'Sullivan, a member of I.R.A. headquarters, reminded the men that their suffering would "be remembered in the annals of the victories of our army."38 In the case of political imprisonment and hunger strike, one's duty was reinforced by peer pressure. Reminiscent of the walls of stone and concrete that surrounded them, this duty was in many cases inescapable.

Enforced, or coercive loyalty was a phenomenon felt not only by revolutionary participants, but by Irish civilians as well. Terror tactics aimed at civilians not only pressured communities to align themselves with rebels but also contributed to the social and political division and trauma that would be experienced in the post-revolutionary years. Irish citizens with dual-loyalties, those maintaining sympathy with Britain, as well as Irishmen serving the Crown in some capacity, naturally suffered most. In particular, as the eyes and ears of the British administration, members of the Royal Irish Constabulary endured assassination attempts, intimidation, and social ostracism. A 1919 article published in "An t-Óglach," the war journal of the I.R.A., stated that the declared Irish Republic "justifies Irish Volunteers in treating the armed forces of the enemy - whether soldiers or policemen - exactly as a National Army would treat the members of an invading army." Similarly, a 1920 circular to the R.I.C., issued by Sinn Féin, stated that Irish constables were enforcing Britain's laws "without a clear understanding of what they were doing." Every Irishman, it continued, "should get a chance of becoming a loyal citizen of the Irish Republic," and encouraged police to quit the force.39 The Sinn Féin Executive promised that, by resigning, constables would have their enemy status lifted, be found employment, and be compensated in times of hardship.40 Such propaganda was enforced through an equally strong social component. Grocers were ordered by the I.R.A. not to sell food or fuel to policemen; sharing a pew with a constable during Mass was to be avoided. Women of Cumman na mBan were told: "Avoid all social intercourse [with the police]. No salutations. No social contact. If they attend, you leave."41

Ostracism, intimidation, murder, and the mental distress it caused to constables, took its toll. Many policemen refused to do their duty - or did it ineffectively. Others simply kept their heads down and looked toward retirement. Still others couldn't wait that long; hundreds quit the force during the revolutionary period, as episodes of terror became more frequent.42 Similar to the police, Irish civilians and civil servants, whose convictions had been formed prior to the "new certainties embraced by the gunman,"43 were identified as disloyal to the more recently conceived standards of the nation. Sean O'Faolain refuted the notion that policemen, such as his father, were "traitors" to Ireland:

"Men like my father were dragged out in those years, and shot down as traitors to their country. Shot for cruel necessity - so be it. Shot to inspire necessary terror - so be it. But they were not traitors. They had their loyalties, and stuck to them."44

The redefining of loyalty and treason throughout the revolutionary period helped to radicalize portions of Irish society, particularly Sinn Féin, the I.R.A., and those that supported them. The enduring question remains the extent to which loyalty to the revolutionary program was genuine, as well as the degree to which sympathy and support of the republican campaign was extracted through terror and intimidation. These factors may never truly be known.

Nevertheless, the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1922,45 which ended hostilities between Irish and British forces and secured an Irish Free State of limited autonomy, as well as the results of the Pact election that followed in June, which returned a majority of pro-Treaty candidates, signifies that Dáil Éireann and the Irish population favoured a compromised level of autonomy and peace rather than resumption of war. This decision, however, had enduring national consequences. While the Anglo-Irish War popularly succeeded the Great War as nationalist Ireland's chosen trauma, its outcome, which left Ireland technically free but divided from portions of Ulster, contributed to further social and political division.

Select trauma in the Irish Free State

When the Irish Free State was formed, the task of restoring order and normalcy to a war-weary and, in many ways, psychologically distressed population lay at the feet of several capable but collectively inexperienced statesmen.46 This was made all the more difficult by the fact that the Irish civil war, which lasted nearly eleven months from June 1922 to May 1923, exacerbated old divisions and created new ones. As Tom Garvin commented, the national split over the Treaty produced "mutual contempt" as pro- and anti-Treaty factions labeled one another as "disloyal to the national cause," creating in the minds of many republican purists Ireland's own Dolchstoßlegende.47

The immediate consequences of the split was that it denied the Free State administration the talents of a number of gifted soldiers, organizers, and politicians, who formed the nucleus of anti-Treaty Sinn Féin and I.R.A. In effect, republicans were branded antagonists within the state's foundation narrative. As a result, they became increasingly disconnected from the Free State under the presidency of W.T. Cosgrave, joining the metaphorical ranks of Irish veterans of the Great War, who, too, struggled to find their place in the new state.

Irish veterans of the Great War were demobilized to an Ireland significantly changed from that which they had left only years before. Since the Armistice of November 1918, the campaign to establish official memory of the Great War in Ireland - to recognize it as a national trauma whose participants had contributed to securing both Irish autonomy and peace in Europe - had been fought by a variety of individuals and groups.48 The dawn of popular republicanism may have eclipsed public support for the Great War and its veterans (or bullied it into silence), but public sentiment was difficult to fully suppress. Observations of the first anniversary of the armistice were unofficially marked in Dublin by small remembrance gatherings, and two minutes of silence.49

Appeals for recognition of Irish veterans of the British Army caused controversy prior to and following the establishment of the Free State, and were interpreted by many as challenges to nationalist orthodoxy. This occurred through a variety of mediums, some peripheral to the soldiers themselves. For instance, Jane Leonard has highlighted division between the student bodies of Trinity College Dublin and University College Dublin, which supported and stymied recognition of veterans' sacrifices, respectively.50 Jason Myers has recently surveyed the extent to which Remembrance Day events often incurred backlash from republicans. For instance, in November 1925, reels of the British film Ypres were stolen at gunpoint from Dublin's Majestic Theatre "in the name of the republic"; the theatre's lobby was later bombed (after replacement reels were located) in an effort to deny any public formation of Great War memory in Ireland.51 Overall, post-independence Ireland marginalized the influence of the Great War on, and in Irish history in favour of the revolutionary narrative. The result was an Ireland that actively confined its Great War veterans to the periphery of state memory, subjecting them to a form of trauma different than that which they experienced between 1914 and 1918 - one of exclusion and internal banishment.

In some ways, republicans' feelings of betrayal following the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, and their suppression by Free State forces during the civil war, helped them to articulate their own chosen trauma. The Free State thus became a symbol of subjugation against which republicans rallied throughout the 1920s and after - one that, for many, represented continuity with the former British administration. Such accusations were voiced in the wake of Free State legislation aimed at ending the civil war, and suppressing republicanism in its aftermath.52 This interpretation of continuity extended to the new security functions of the state, including police and prisons. Members of An Garda Síochána (Civil Guards, or Guardians of the Peace), for instance, were demeaned in similar terms to those directed at the Royal Irish Constabulary during the revolutionary period,53 while groups that supported republican political prisoners made reference to continuity in their lambasting of the Free State prison policy. Maud Gonne MacBride, writing for the "Political Prisoners' Committee" in 1927, illustrated the Free State's direct connection with the previous administration, citing the staffing of Ireland's prison service with ex-British warders and ex-British soldiers who "delight in taking it out of Irish Republicans whom they once feared."54 Excerpts from correspondence of the Women's Prisoners' Defence League, founded in 1922 to lobby for the release of political prisoners, echoed these observations:

"The Free State took over the English prisons at their worst. Built primarily to hold Irish rebels for whom nothing was too bad, no attempt at reform was made, and the Free State had made no change in the vicious system."55

The various components that combined to form Irish Free State society had been significantly influenced by the dual upheavals of the Great War and Irish Revolution that had preceded its foundation of the new state. In some respects, the dynamic of loyalty that had been formed, refined, and which had evolved during this period produced numerous personal and ideological fallouts and contributed to several dynamics of victimization. Some of the most noticeable were those suffered by two differently marginalized groups of veterans: those of the British army during the Great War, and those of the anti-Treaty I.R.A.

Conclusion

Writing for the Irish Times in 2013, Conor Mulvagh argued, "the impact of Ireland's revolution cannot be measured in purely statistical terms. The deepest impact was psychological." Similarly, Edward Madigan recently advocated that though they were remembered as separate national experiences, the Great War and Irish Revolution are intrinsically linked, as were many of their respective participants. It was nevertheless often difficult for Irish society to recognize the dedication and sacrifices made by all of its soldiers as worthy of standing on equal commemorative footing. I would argue that the formation and evolution of nationalist loyalty played a significant role in shaping personal identities and outlooks, and moulding a distinct republican mentality during the Great War and Irish Revolution. This, in turn, helped to facilitate division on the question of which conflict, the Great War or Irish Revolution, would represent Ireland's national trauma.

There are natural drawbacks to using loyalty as a method to examine violent revolutionary behaviour. Numerous internal and external considerations prevented individuals from acting solely upon what might be observed as immediate moral or patriotic convictions, or genuine loyalty. In other words, ideals cannot be said to have held exclusive authority over one's actions. In fact, considerations of personal safety, disinterest or a sincere desire not to be involved in revolutionary exploits of the period perhaps account for far more inactivity than has been previously explored. Therefore, conclusions on the nature and extent of loyalty in Irish society during the revolutionary period must weigh the variety of penetrating cultural factors against more immediate, sometimes coercive, influences. Broadly articulated national sentiments do not account for regional, communal and individual variables, which are more truly representative of the real impact of the Great War and Irish Revolution on Irish society.

- 1. George Fletcher, Loyalty: an essay on the morality of relationships. Oxford University Press, New York 1993. S. 9; 33-35. – The website’s editors are grateful for Jennifer Laing’s support in preparing this text for publication.

- 2. Andrew Oldenquist, Loyalties. In: The Journal of Philosophy, vol. LXXIX, no. 4, (April 1982), S. 177-8.

- 3. Robert Gerwarth/John Horne (Hrsg.), War in peace. Paramilitary violence in Europe after the Great War, Oxford 2012. In particular, Julia Eichenberg, Soldiers to civilians, civilians to soldiers: Poland and Ireland after the First World War. In: Gerwarth/Horne, War in peace. S. 184-99; and Anne Dolan, The British culture of paramilitary violence in the Irish War of Independence. In: Gerwarth/Horne, War in peace. S. 200-215.

- 4. While initial enlistment returns reveal that recruits came from both organizations, those not affiliated with the Volunteer movement also enlisted in great numbers. David Fitzpatrick has explored how enlistment was in many cases simply an expression of loyalty to one’s friends and family, rather than a display of popular militancy. David Fitzpatrick, Home front and everyday life. In: John Horne (Hrsg.), Our war: Ireland and the Great War, Dublin 2008. S. 131-42.

- 5. Tom Barry explained and justified violence in such terms: "Without Dáil Eireann there would, most likely, have been no sustained fight, with moral force behind it." Tom Barry, Guerrilla days in Ireland. Anvil Books, Dublin 1962 edn. S. 11.

- 6. David Fitzpatrick, The logic of collective sacrifice: Ireland and the British Army, 1914-1918. In: The Historical Journal 38, 4 (December, 1995), S. 1017; Jane Leonard, The twinge of memory: Armistice Day and remembrance in Dublin since 1919. In: Richard English/Graham Walker (Hrsg.), Unionism in modern Ireland: new perspectives on politics and culture. MacMillan Press Ltd, London 1996. S. 99.

- 7. The Boer War (1899-1902) helped rekindle nationalists’ public opposition to Britain. Many drew parallels between the position of Ireland and the Boer republics, as evident in police reports that cited nationalist activity as having been reignited by the South African war. See Royal Irish Constabulary Inspector General’s monthly report, January 1900, Sir Andrew Reed to Sir David Harrel (Under-Secretary). The National Archives, Kew [hereafter T.N.A.], Colonial Office [hereafter C.O.] 904/69; Justin Dolan Stover, Periphery of war or first line of defense? Ireland prepares for invasion, 1900-15. In: Francia: Forschungen zur westeuropäischen Geschichte, vol. 40 (2013). S. 385-96.

- 8. Statement of Eugene Bratton. Bureau of Military History [hereafter B.M.H.], Witness Statement [hereafter W.S.] 467; statement of Patrick Meehan. B.M.H., W.S. 478; statement of Liam O’Riordan. B.M.H., W.S. 888.

- 9. Statement of Liam O’Riordan. B.M.H., W.S. 888.

- 10. John Redmond to Herbert Asquith, 5 August 1914. National Library of Ireland [hereafter N.L.I., John Redmond papers, MS 15,520.

- 11. In: Irish Independent, 21.09.1914.

- 12. Casement to unknown, 28 September 1914. N.L.I., Florence O’Donoghue papers, MS 31,131.

- 13. "Why I came to Germany," Roger Casement, 16 December 1915 (N.L.I., Casement papers, MS 13,085/11).

- 14. Irish Volunteer, 22 August 1914.

- 15. Fianna Fail, 26 September, 10 October 1914. Redmond was not wholly conciliatory to the British position. As Brian Hanley has recently commented, Redmond and the Irish Party had strong connections with Fenianism and must not be solely identified as parliamentarian. Brian Hanley, Redmond and home rule. Irish Times, 26.08.2014.

- 16. "A ballad of European history," n.d. (N.L.I., Barton scrapbook, MS 5,637)."

- 17. In: Cork Celt, 17.10.1914.

- 18. Kevin Kenny, The Irish in the empire. In: Kevin Kenny (Hrsg.), Ireland and the British Empire. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004. S. 109.

- 19. Compiled from "Table III A, recruiting statistics," various dates. N.L.I., John Redmond papers, MS 15,259.

- 20. Fitzpatrick, Home front. In: Horne (Hrsg.), Our War. S. 134.

- 21. Moreover, the Rising, and the Proclamation of the Irish Republic that articulated its impetus, acted to commandeer the loyalty from the Irish nation. It stated: "The Irish Republic is entitled to, and hereby claims, the allegiance of every Irishman and Irishwoman." "Proclamation of the Republic of Ireland, 1916." Arthur Mitchell and Pádraig Ó Snodaigh (eds), Irish Political Documents 1916-1949. Irish Academic Press, Dublin 1985. S. 17-18.

- 22. Peter Hart, The I.R.A. and its enemies: violence and community in Cork, 1916-1923. Oxford University Press, New York 1998. S. 132-3, 148; Joost Augusteijn, From public defiance to guerrilla warfare: the experience of ordinary Volunteers in the Irish War of Independence 1916-1921. Irish Academic Press, Dublin 1996. S. 141.

- 23. Augusteijn, From public defiance to guerrilla warfare. S. 57, 62, 68-9; Hart, The I.R.A. and its enemies. S. 148, 208, 215. See also, Erhard Rumpf and C. Hepburn, Nationalism and socialism in twentieth-century Ireland. Liverpool University Press, Liverpool 1977. Rumpf argues that the social composition of the I.R.A., though certainly varying due to location and circumstances, also varied according to the concentration of Catholic and Gaelic culture in society.

- 24. Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau (trans. Helen McPhail), Men at war 1914-1918: national sentiment and trench journalism in France during the First World War. Berg Publishers Limited, Oxford 1995 edn). S. 46.

- 25. Hart, The I.R.A. and its enemies. S. 208, 215.

- 26. Fletcher, Loyalty. S. 7, Josiah Royce, The philosophy of loyalty. New York 1916. S. 107-8.

- 27. Joanna Bourke has commented on how the "love for one’s comrades" acts as strong incentive toward violent behavior. Joanna Bourke, An intimate history of killing: face-to-face killing in the twentieth-century. Basic Books, UK 1999. S. 129-30. See also, Anne Dolan, "The shadow of a great fear": terror and revolutionary Ireland. In: David Fitzpatrick (Hrsg.), Terror in Ireland, 1916-1923. The Lilliput Press, Dublin 2012. S. 26-38; and Jane Leonard, "English dogs" or "Poor Devils"? The dead of Bloody Sunday morning. In: Fitzpatrick, Terror. S. 102-40. For instances of mental trauma stemming from experiences of revolutionary violence, see Peter Berresford Ellis, "The Mental Toll of Revolution." Connolly Publications Ltd, London 2003 at www.irishdemocrat.co.uk/features. See also Statements of Tom O’Grady (BMH, WS 917), S. 5-6, Seamus Kavanagh (BMH, WS 208), S. 12, Garry Holohan (BMH, WS 336), S. 4-5, Vincent Ellis (BMH, WS 682), S. 2.

- 28. David Fitzpatrick, The geography of Irish nationalism, 1910-1921. In: Past and Present 1xxviii (February, 1978), S. 113-44; Peter Hart, The geography of revolution in Ireland, 1917-1923. In: Past and Present clv (1997), S. 142-76.

- 29. Justin Dolan Stover, Terror confined? Prison violence in Ireland, 1919-1921. In: Fitzpatrick, Terror, S. 219-35; William Murphy, Political Imprisonment and the Irish, 1912-1921. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2014.

- 30. L.J. Blake to Chairman, 29 January 1919. National Archives of Ireland [hereafter N.A.I.], G.P.B. 1919/826.

- 31. "Oglach na h-Eireann, special general orders, G.H.Q., Dublin," 13 January 1919. N.A.I., G.P.B. 1919/2026. In general, prison riots and hunger strikes were left the discretion of prison leaders rather than G.H.Q. This particular order was issued only after rioting had begun at several prisons, including Cork, Galway, Limerick, and Mountjoy.

- 32. Felix Connolly to Charles Munro, 26 January 1920. N.A.I., G.P.B. 1920/652 (with 987).

- 33. Gallagher and thirty-five others commenced hunger strike on 5 April 1920; they were joined by others on successive days until their number totaled nearly ninety.

- 34. Frank Gallagher, Days of fear. John Murray Publishers, London 1928. S. 47. Ellipses are a staple of Gallagher’s narrative. Few of the above quotes were amended from the original text.

- 35. Gallagher, Days of fear. S. 54-5.

- 36. Gallagher, Days of fear. S. 15.

- 37. Gallagher, Days of fear. 147-8."

- 38. Fr. Albert to Maurice Crowe, 13 Apr. 1920; Gearoid O’Sullivan to Maurice Crowe, 15 Apr. 1920. Irish Military Archive [hereafter I.M.A.], CD 208/2/9;10.

- 39. "Appendix IV: Copy of Sinn Féin circular to members of the R.I.C., 27 July 1920," Interim Report of Committee of Inquiry into resignation and dismissal of R.I.C., 3 May 1923. N.A.I., TAOIS, S 1764.

- 40. "Appendix IV: Copy of Sinn Féin circular to members of the R.I.C., 27 July 1920," Interim Report of Committee of Inquiry into resignation and dismissal of R.I.C., 3 May 1923. N.A.I., TAOIS, S 1764.

- 41. W.J. Lowe, The War Against the R.I.C., 1919-21. In: Éire-Ireland 37, nos 3/4 (Fall/Winter 2002), S. 84-5; Arthur Mitchell, Revolutionary government in Ireland: Dáil Éireann 1919-22. Gill & MacMillan, Dublin 1995. S. 37; 69; David Fitzpatrick, Politics and Irish life. Cork University Press, Cork 1977. S. 10-11.

- 42. Sir Hamar Greenwood, British Chief Secretary for Ireland, announced in Parliament in August 1920, that the RIC were resigning or choosing to retire at a rapid pace; approximately 560 quit the force between June and July 1920.

- 43. Hart, The I.R.A. and its enemies. S. 18.

- 44. Sean O’Faolain, Viva moi! An autobiography. Little Brown, London 1965 edn). S. 35-6. Also quoted in Hart, The I.R.A. and its enemies. S. 1. Hart also identified the loyalty of other police to their duty, and how many ex-soldiers in Cork remained loyal to the Crown. S.3; 16-17.

- 45. "Anglo-Irish agreement of 6 December 1921," Mitchell & Ó Snodaigh (eds), Irish Political Documents. S. 116-21.

- 46. For observation of the extent of psychological distress in Irish civilians see statement of P.J. Swindlehurst, a private with the Lancashire Fusiliers, who stated of the people of Dublin: "The constant shootings, hold ups and raids are leaving their marks, one can tell by the earnest whispered conversations, the darting furtive glances, and the ever on the alert look, that many don’t know what will happen next." Diary of J.P. Swindlehurst, 12 January 1921. London, Imperial War Museum, J.P. Swindlehurst papers, P538.

- 47. Tom Garvin, The aftermath of the civil war. In: The Irish Sword vol. XX, no. 82 (winter 1997) S. 388.

- 48. See George Boyce, The sure confusing drum: Ireland and the First World War, Inaugural lecture, 8 February 1993. University College of Swansea, 1993; Keith Jeffrey, Echoes of War. In: Horne (Hrsg.), Our War, S. 261-275; Nuala C. Johnson, Ireland, the Great War and the geography of remembrance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2003, particularly chapter three, Parading memory: peace day celebrations, S. 56-79.

- 49. Leonard, The twinge of memory, S. 102. Leonard also notes how some shopkeepers were themselves bullied into observing the two minutes of silence by members of the Auxiliary police, providing further evidence of civilians being coerced, this time in support of the British army rather than the I.R.A.

- 50. Leonard, The twinge of memory, S. 100-101.

- 51. Jason Myers, Great War and memory in Irish culture, 1918-2010. Maunsel and Company, California 2013. S. 194.

- 52. See: clauses and definitions of seditious activity within This Act may be cited as the Public Safety (Emergency Powers) Act, 1923 and the Treasonable Offences Act, 1925; Martin Maguire, The civil service and the revolution in Ireland. "Shaking the blood-stained hand of Mr. Collins." Manchester University Press, New York 2008. S. 174; Ciara Meehan, The Cosgrave Party: a history of Cumman na nGaedheal, 1923-33. Royal Irish Academy, Dublin 2010). S. 37, 93.

- 53. Brian Hanley, The I.R.A., 1926-1936. Four Courts Press, Dublin 2002. S. 78-9.

- 54. Maud Gonne MacBridge, "Strike of Republican Prisoners," 20 June 1927. New York Public Library, International Committee for Political Prisoners records, Reel 7: Folder: 17, 1931-1932.

- 55. "Statement on Free State Prisons and Political Prisoners," Women Prisoners’ Defence League, 25 July 1931. New York Public Library, International Committee for Political Prisoners records, Reel 7: Folder: 17, 1931-1932.